“ Markewarkes Church in Mangeshi ” A Historical Glimpse of the Past

Markewarkes Church in Mangeshi

“A Historical Glimpse of the Past”

By: Francis K. Khosho

The village of Mangeshi is home to the Markewarkes Church, which serves as a significant historical symbol to all of its parishioners, both past and present. It is important for our community members to continue to delve into its history and understand how such a notable landmark became and continues to be the epicenter of our village.

Our ancestors established the presence of religion in the village of Mangeshi long before formal Christianity settled into the region. Markewarkes Church dates back to the beginning of the Christian presence in Mangeshi. It was built on the same plot of land as the old Zoroastrian temple (Beth Mkoshi) signifying its religious prominence. Presently, the church continues to be used as a place for public worship and formal church services, including: baptisms, communions, weddings and funerals. This article is an effort to more closely examine how the church was built and what life was like in Mangeshi during this time.

Syriac (Neo-Aramaic) speakers, descendants of the ancient Assyrian and Babylonian empires, were among the first of those to convert to Christianity. In fact, Syriac was one of the major languages of Christianity from the second to fourteenth centuries. In the beginning, the church of the first four centuries met in privately owned homes (Roman 16:5, Corinthians 16:19). Later, households and places of business were converted to churches. It is likely that Mangeshnayi in Mangeshi and Christians in surrounding areas converted the Bet Mkoshi (Zoroastrian) temple into a church. This church developed through the years and a new altar (Mathebha) was built in the current church yard in 1843 (See “Nineveh and its Remains” Vol. 1, p. 228, Austen Henry Layard). The north wall of the Bet Mkoshi temple remains intact and is currently the south wall of the Markewarkes Church, which was formally built in 1929.

The original Markewarkes Church was a centuries old church, built with great care. However, the church, due to its age, began to deteriorate over time. It was also exceptionally vulnerable to adverse weather conditions from the coldest of winters to the warmest of summers. Winter storms in particular would bring large quantities of snow, strong winds and rain. This would take its toll on the church, creating problems with the roof and failure of the roof trusses, which would have eventually caused the collapse of the old church.

Under the leadership of Father Hermiz Keji, a meeting was called to discuss the deteriorating condition of the church and the immense need for reconstruction. It was a major financial and labor-intensive process but it was necessary for the church’s survival. Funds were raised by all villagers, with everyone contributing within their means. Villagers also offered their assistance through labor, helping with the various physical tasks.

The demolition of the old church was announced at Sunday mass, but many were fearful that they would be destroying God’s house and upsetting St. George (Markewarkes). Father

Hermes Keji addressed his parishioners and assured them that St. George and God would be thrilled about a bigger and better church to house their faithful community. Father Keji went on the roof of the old church, took with him a shovel to begin the demolition process and said, “It is going to happen. God is going to do it.”

The drum and zurna were beating, persistent and unchanging. Their sound was no longer a separate thing from the village noise, but rather the pulsation of the village’s heart. The village was filled with excitement as two of the finest masons, Khal Odesho Shamami and Kyoru, were called in from the Sapna area to assist in the structural development of the new church. Additional experts in the areas of arches, archways and other architectural matters were also brought in from the city of Mosul to provide insight and advice during the construction of important joints. A team of men were tasked with cutting large chunks of limestone from the Mangeshi mountains and bringing them back to the village. A team of women worked side by side with the men, contributing significantly to the construction of the church, by preparing supplies to transport soil and water. This was in addition to the preparation of food and drinks for the workers.

And so, construction began on one of the most prestigious churches in the area – a structure that would be much larger than any other house in the village. The structure was primarily built with limestone. The chunks of limestone were broken down by the assigned masons into smaller pieces, trimmed and reshaped to the aesthetic requirements of the church. The limestone blocks were then transported by mules and donkeys to the construction site. A pit dome was dug deep into the ground and was probably made of stone too. Layers of wood and limestone filled the pit and were called atony. Burning limestone, creating a quick calcium oxide limestone (Kelsha), was soft when first mixed, but with time hardened through its absorption of carbon dioxide. The building was 24×16 meters, which included a nave or hall and an arched roof. Two side aisles flanked the nave, which was separated by a row of regularly spared columns. There were two entrances, both facing south. The central part of the church building, intended to accommodate most of the congregation, was rectangular and separated from the main chancel (Mathepha). Adjacent aisles had pillars (a total of 12), which were called “Mary Sultana of the Rosary Altar.” The altar to the south was called St. George (Markewarkis) and was the location where all of the baptisms took place. The altar to the north was called Father Ibrahim (Baban Uraha).

The most important and difficult task for the masons was the arched roof, which constituted the basis of the church architecture. The arch was a curved structural form composed of wedge-shaped stones. Our dear friends, Dr. Rabi and Jalal Shabo, were right – in that – paths were formed during the building of arches between the pillars of the church. Arches were the basis of church vaults. The continuous barrel vault was constructed by extending an arch across an expanse from pier to pier, creating a ceiling that had a concave appearance (See Medieval Churches, Sources or Forms, Valerie Spanswick, khanacalemy.org). This is similar to the look of our church’s arched roof.

The old bell (Naqosha) was replaced with the current, new bell in 2015, after eighty-six years of service. It continues to ring out to the hearts of villagers from its steeple (Qoba). It will ring, calling parishioners to church every day. It rings during happy occasions, such as the Bishop’s visit, and with its solemn tone, it also rings to accompany times of sorrow, like funerals. The old bell was relocated to the Nashmoni cemetery oratory (or Chapel) where our cherished, loved ones are buried.

After ninety years, the church due to its age, began to deteriorate over time. The roof and the walls needed repair both inside and out. This time, Father Yuoshia Sana and Myer Hanna Gullo called for a meeting with the village’s hard-working youth volunteers. Over ninety volunteers showed up and under the leadership of Adeel Hanna, began their work on May 19, 2019 and were able to finish on October 24, 2019. These youth volunteers selflessly gave their time to remodel the most ancient piece of our ancestor’s history. We are thankful to everyone who played a part in making this possible. Here is a list of volunteers: Salem Franso Jona, Adele Hanna Gullo, Raed Hanna Matti, Issa Jihad Issa, Wissam Toma Mansour, Eugene Gwargis Toma, Yusef Bersfi / altars, Zulaka Bersfi / altars, Yvonne Bersfi / altars, Youssef Pato Abbou, Fali Yosef Pato, Ghazwan Naguib Hanna, Ronnie Daniel Abbou, Johnny Naguib Mikho / Electricity, Ishoe Yunan Sepo, Naser Yunan Smuqa, Nasrat Yunan Smuqa, Devi Naguib Yonan, Levi Naguib Yonan, Evas Gullo Matti, Isho Fadel Isho, Fadi Isho Issa, Sherzad Ahmed Ibrahim, Basima Slewo Elijah, Sheehan Eilish / replenish furniture, Raed Paul Mikho, Ramses Polis Mikho, Diyar Ghalbishi, Yosef Adeeb Dohuki, Sargon Nissan, Kanye Plave, Iwan Polis Toma, Majid Daniel Abbou, Adel Isaac Marqos, Peter Gebriel Boutros, Jim Essam Cherko, Bernard Essam Cherko, Kwarkis Essam Jerko, Milan Issa Hanna, Aseel Sobhi Esho, Eiffel Amjad Ablehat, Jalal Shabu Hakim, Daly Yosef Shamika, Sami Franso Chona, Sarmad Sami Franso, Ramez Sami Franso, Gwarkis Haitham Mansour, Ever Amjad Ablehat, Alvire Amjad Ablehat, Seaview Sabah Gem’a, Dawood Hormuz Markho / carpentry, Samer Jabo Yunnan, Haval Korkis Esho, Fallen Polis Esho, Haitham Mansour Pato, Philip Esha Yacoub, Evan Matti Mansour, Ethan Warda Bafro, Lovin Jihad Issa, Ramson Benjamin, Salam William, Dillon Esho Sepo, Tony Daniel Abbou, Fadi Toma Odisho, Frank Toma Odisho, Marqos Aseel Subhi, Melad Naser Yonan, Raven Raid Hanna, Mark Wisam Touma, Dawood Salem Franso, Danny Salem Franso, Fadi Wilson, Nashwan Naji Mikho, Kalus Emmanuel Toma, Marvin Amir Esho, Gewarkis Omid Uraha, Marius Naguib Issa, Qaedar Gewarkis Mikho / Smith, Michael Gewarkis Mikho / Smith, Laith Merky / Helan, Hilal Merky / Helan, Revan Aqrawi / Helan, Rami Aqrawi / Helan, Matti Leith Merky / Helan, Ronaldo from Hazar Jute / Alabaster, Bakhtiar Halabji / sculptor, Ibrahim Youssef Oraha, Stephen Ibrahim Yosef, Martin Andrawis Odisho, Marvin Andrawis Odisho, Mark Andrawis Odisho, *Funds for remodeling were raised by parishioners in Mangeshi and Mangeshnayi all over the world.

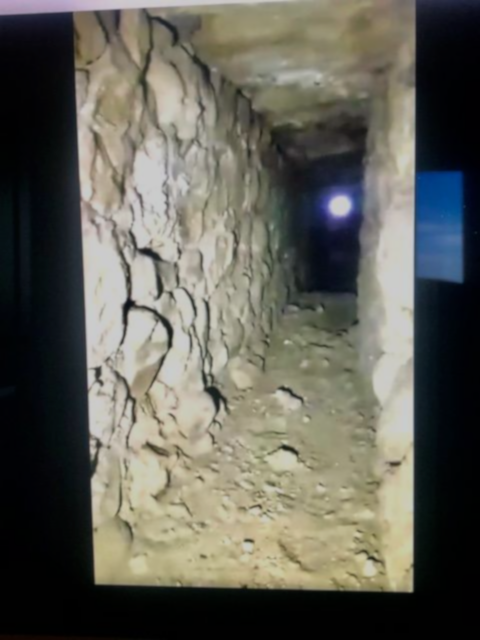

Recently, a video has circulated of the corridors (Dahleza) located on the top of the church walls between the ceiling and the roof. This video was created by our dear friends, Salim

Franso and Fadi Esho and has sparked a thoughtful conversation about something that has been unknown for decades. Some of our supportive community members, Hanna Shamon, Dr. Rabi, Jalal Shabo, Ibrahim Ossi and others have generated many thought-provoking ideas and considerations about what the purpose of the corridors were. Were the corridors placed there strategically as a place to hide? Or, did they play a specific role in the church’s acoustic properties? I delved into some research that could potentially explain their purpose with some resources available and discussions with older members of our community.

The video from Salim Franso and Fadi Esho showed that the corridors in the ceiling of the church did not provide much room to stand up or move around. We were told by our parents’ generation that many of our homes contained hiding places that were built in case of a raid.

They were built in attics and inside walls.

Raiders would tap on the walls to see if they were hollow and tear up the floors to search underneath the home. So, it does make sense that perhaps the churches corridors were being used in emergency situations as a hiding place.

However, another idea or theory is also very plausible and the research certainly supports it. This idea is that acoustic pottery was placed inside the churches corridors in order to support the sound function of the church. Due to the church’s width and length, and certainly before the invention of microphones, something needed to be put into place in order to assist parishioners seated throughout the church to better hear the priest. Acoustic pottery has been found furnished into the walls and vaults of many ancient Byzantine, Europe and Scandinavian churches. The earthenware pots were found with their orifices turned toward the interior of the buildings (See Walford’s Antiquarian Magazine and Biographical Review). They are believed to have been placed there in order to improve the sound of singing, etc. (See Acoustic Pottery, Wikipedia). Another similar finding was made at East Harling Church in North folk, England where four jars were brought to light during repairs to the roof. Another church, near Maidstone, Kent, uncovered forty-eight to fifty earthenware pots embedded in the wall on both sides of the church that were used to improve acoustics (See Antiquities and Curiosities of the Church, p. 34-43, William Andrew). I was told by aunt Kato Ado Be’Daweth, that she was about eight years old at

the time of the new church’s construction. She said that during the Sunday mass, Father Hermiz

asked the villagers to donate earthenware-type pots, those used by the villagers as storage

containers, and bring them to the construction site. She remembered that he said the pots were going to be used by the mason during construction to help with sound amplification in the church (Braqala). She could not remember what happened to the pots once they were delivered, or where and if they were in fact installed, but she does have a specific memory of men and women taking their water pots (Kadoni), Leni and even Lenyatha to the church site. In all probability, this was in support of our churches sound system, similar to those mentioned above with other churches. These earthenware jars could be in the interior walls of our church and covered by old plaster (Kelsha). They could be laying on their side with their mouths directed to the inside of the church, covered over with a piece of slate, and hidden behind the plaster.

This video recording has resulted in a very special conversation about one of our village’s oldest landmarks. I would like to give special thanks to Salim Franco and Fadi Esho for taking us on this journey and sharing their video. I would also like to thank our dear friends, Sam Desho, Warda Essa, Dr. Rabi, Jalal Shabo, Ibrahim Ossi and Hanna Shamon for their valuable information, time and discussion on this subject. It is my hope that this article contributes in some way to this most interesting exchange. Blessings to you all.

Francis K. Khosho, California